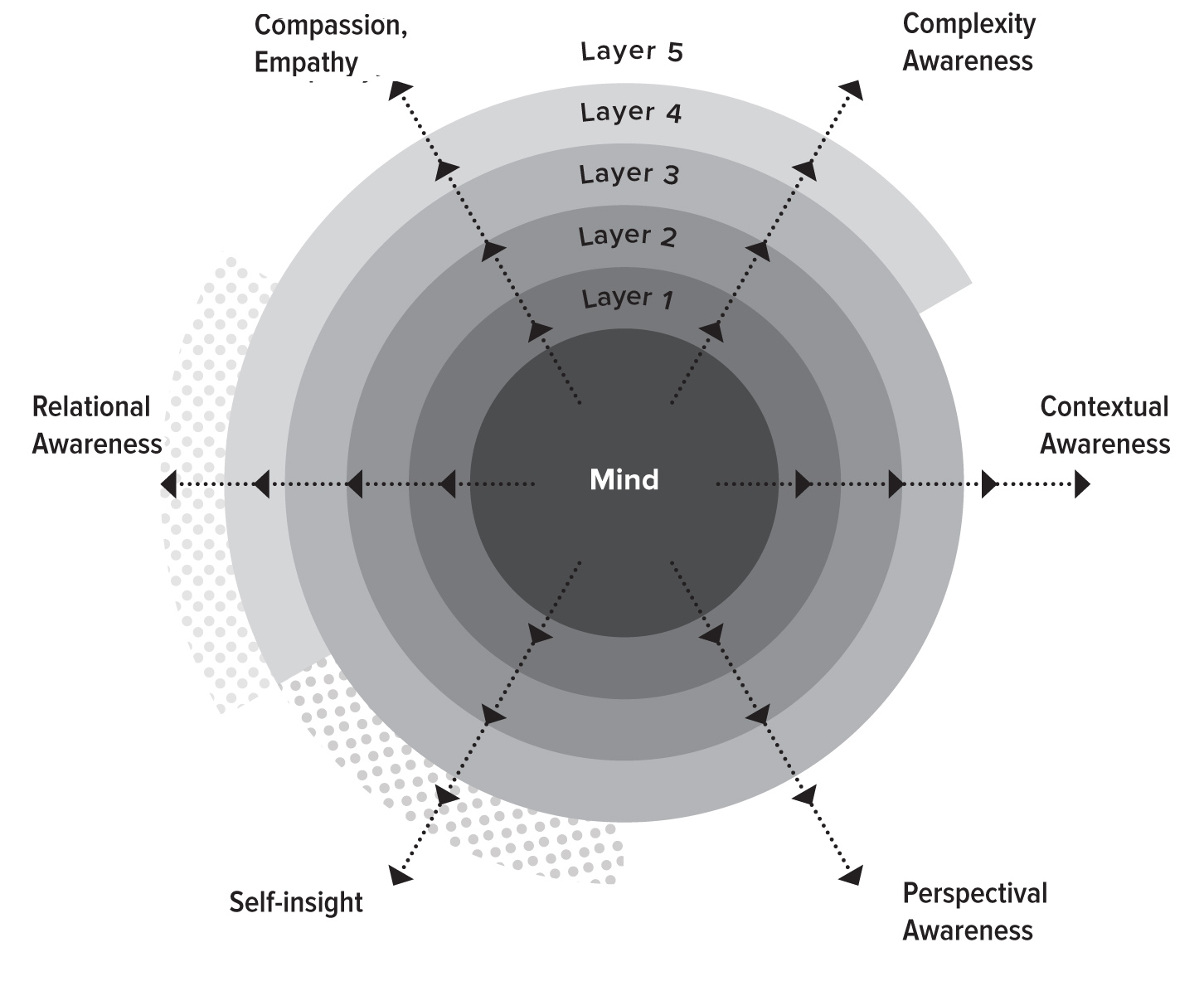

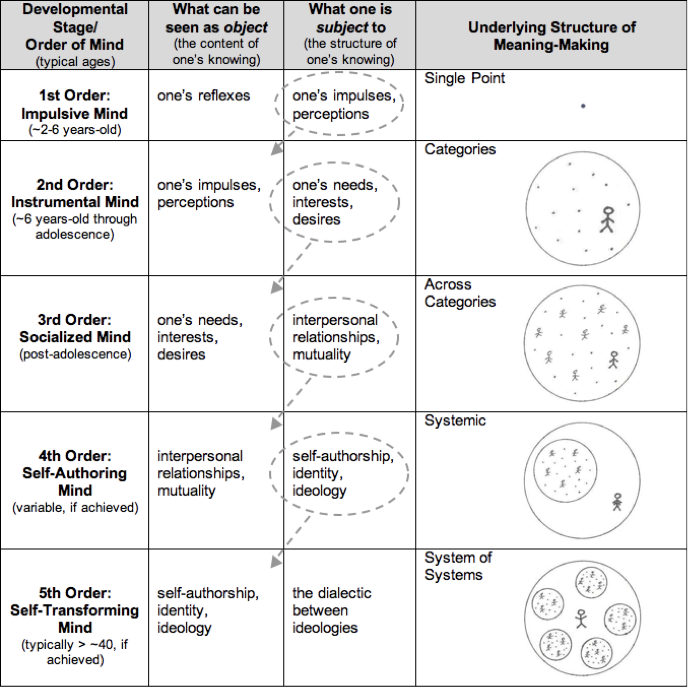

In his book The Evolving Self: Problem and Process in Human Development (1982), Kegan posits six stages or evolutionary balances the self could employ to organize experience and make meaning: (0) Incorporative; (1) Impulsive; (2) Imperial/Instrumental; (3) Interpersonal (4) Institutional/Individual; (5) Inter-Individual/Inter-Institutional. Although the first phase characterizes infancy, these stages stretch well beyond childhood, the period so overemphasized by other developmental theorists. Kegan’s balances are not mere milestones to sprint past on a linear race to life’s final finish. They can be envisioned as nested layers of context—veritable interrelated Russian dolls of conscious awareness—from which the self, once embedded, organismically emerges, always with increased mental complexity and, consequently, with an upgrade in perspective.

Transformation, however, is never painless. Elaborating on the Piagetian concept of decentration, what might seem superficially to be an agreeable levelling up to the next order of consciousness actually, in Kegan’s view, involves the destabilizing loss of one’s center of balance—departure of the very subject of one’s being. During the transition between stages, the center of one’s self is removed and relegated to the forefront of one’s perceptual field, where this former subject (i.e. what one is) can be examined and utilized as an object (i.e. what one has).

Once only looked through, this former lens of self can now looked at, as the middle issues out to the margins. Each successive center is constructed, defended, subordinated, surrendered, and reconstituted as the self evolves, while the culture in which the person is immersed plays its own part in this evolution. Taking up where child psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott left off, Kegan elucidates precisely how one’s environment can serve to provide confirmation (holding), contradiction (letting go), or continuity (staying put for reintegration), either facilitating or complicating the enterprise of development.